Where Art Takes a Break

Meeting the public all day. Admired, scrutinised and subjected to selfies. Hanging out with “colleagues” who don’t always agree with your style.

The life of an artwork can be tiresome. Thus, at the end of any exhibition, SAM sends its artworks for a well-deserved break at the Heritage Conservation Centre (HCC). The purpose-built facility in Jurong is where the museum’s collection of artworks is cared for and stored alongside over 200,000 heritage artefacts that make up Singapore’s National Collection.

One of the first persons at HCC to greet the artwork is a conservator like Nahid Martin Pour. She is tasked with assessing its condition after months of public display. Armed with her loupe and hand lamp, Nahid meticulously looks out for anything amiss to report. Flaking surfaces. Scratched edges. Loose connecting joints. These are some common areas of an artwork that could be “damaged” during its installation, transportation and exhibition.

Nahid retouching Dusadee Huntrakul’s He was out there all alone riding the monsoon waves like a champ.

Image courtesy of David Nonnenmacher

“The way a conservator looks [at an artwork] is very detail-oriented,” says Nahid. “You might have a work where every visitor thinks is in perfect condition, but you look at the report and you see hundreds of little notes saying here is a small scratch that you don’t see with bare eyes!”

Most of the time, such faults simply come naturally. Artworks are after all made up of physical materials that react with elements in the environment. Long exposure to sunlight can bleach a print, while changes in temperature can cause a work of different materials to come loose as each expands and contracts at a different rate. In Singapore’s humid weather, one of the biggest issues is the growth of mould. These reasons are why the storage area of HCC is windowless and its temperature and humidity are carefully controlled – creating a stable home for artworks to, well, chill out.

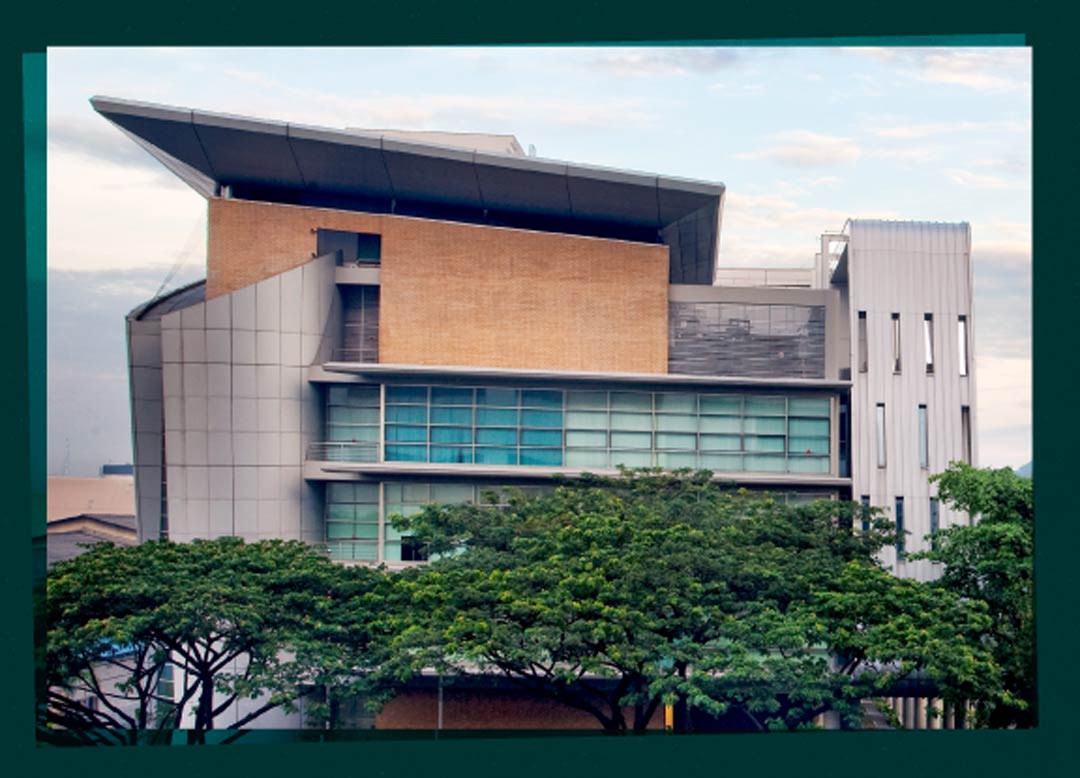

Heritage Conservation Centre

Image courtesy of Heritage Conservation Centre

Contemporary art and its material questions

Regardless if an artwork needs to be “repaired” or not, it is given a good dusting at the very least. Like any good conservator, Nahid works with an assortment of brushes depending on the material she is dealing with. Plant fibre brushes for working with paper. Feathers for delicate surfaces. Her go-to is goat hair brushes because they can take out a lot of dust yet are gentle to the artworks.

“Conservators love materials so we are very precise and use different brushes for different things and purposes,” she says.

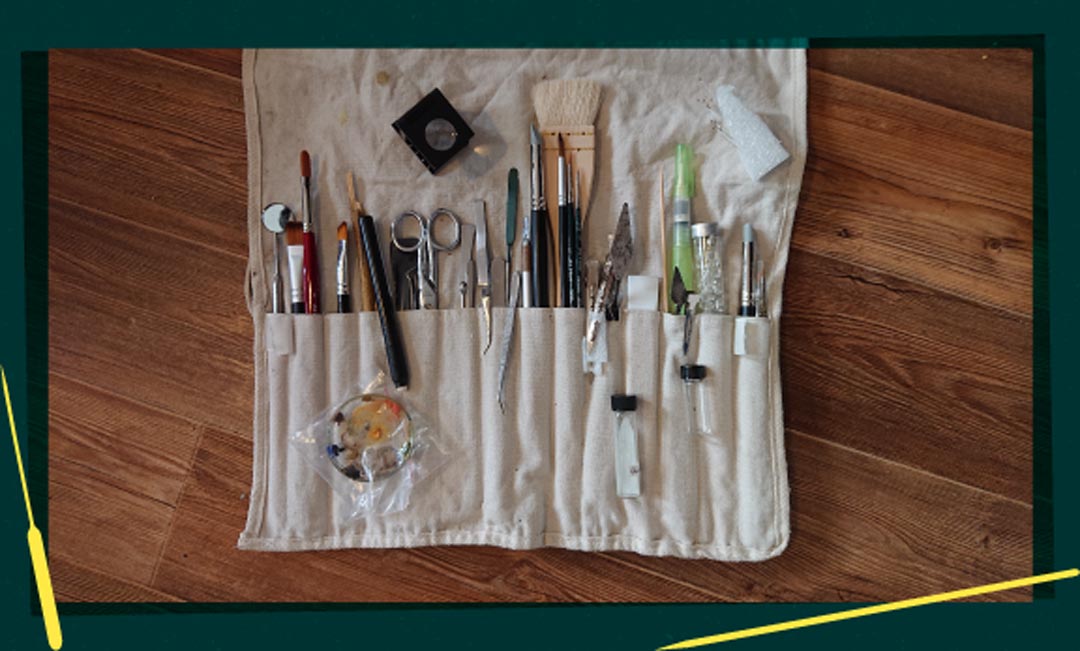

Nahid’s collection of tools, including a goat haired brush (large flat one in middle with wooden handle and white hair).

Image courtesy of Nahid Martin Pour

The variety of materials is especially so for contemporary art. Just ask HCC’s collections managers who have encountered everything from Vincent Leow’s bottle of pee for The Artist’s Urine (1993) to a body garment made of leek by Chia Chuyia for Knitting the Future (2016). Part of the role is creating storage solutions for housing SAM’s collection, and such bizarre objects never fail to amuse and bemuse collections managers such as Marilyn Giam.

“SAM always acquires these interesting works in all shapes and sizes,” she says. “It is not so simple where you put art on a shelf. For contemporary art, the materials are so unpredictable. We always have to think of so many ways to ensure the artwork is well preserved no matter what.”

Burned Victims installation during the FX Harsono: Testimonies exhibition held at the Singapore Art Museum in 2011.

Consider FX Harsono’s Burned Victims, which addresses a tragic riot in 1998 when hundreds died after a rampaging mob stormed a shopping mall and set it on fire. The work consists of 10 wooden torsos the Indonesian artist burnt during a performance as well as charred footwear that were retrieved from the site of the incident. These materials are very fragile, especially so some two decades on. Many of the footwear have profuse flaking and they still retain the pungent smell from the burning.

The state of the artwork presented several questions for collections manager Joanne Lim when she oversaw its loan to the Asia Society Museum in New York in 2017 for an exhibition. Beyond the immediate concern of how to pack it safely for travel, there were longer-term issues. What to do with the artwork as it disintegrates over time? And at what point of deterioration would it no longer be suitable for display?

Joanne holding one of the footwear from Burned Victims.

At the heart of her dilemma is an issue conservators and collections managers face with art: how to ensure an artwork lasts without resorting to interventions that compromise the intentions of its artist. In the case of Burned Victims, the fragility of the objects was the very point of Harsono’s work and it was decided to accept the gradual disintegration of the footwear and even torsos over time.

“The shoes were something we can preserve, although it is under-documented, but the artist and curator felt we shouldn’t,” says Joanne. “It’s kind of sad, but they can consider different modes of presentation (in the future), like using photographs for the shoes, for example.”

Art today, but tomorrow?

Having conversations about the future of an artwork with artists and curators is all part of caring for it. In fact, they happen even before an artwork enters SAM’s collections. When a work is to be acquired, curators consult conservators and collections managers on what is needed to ensure its long-term care.

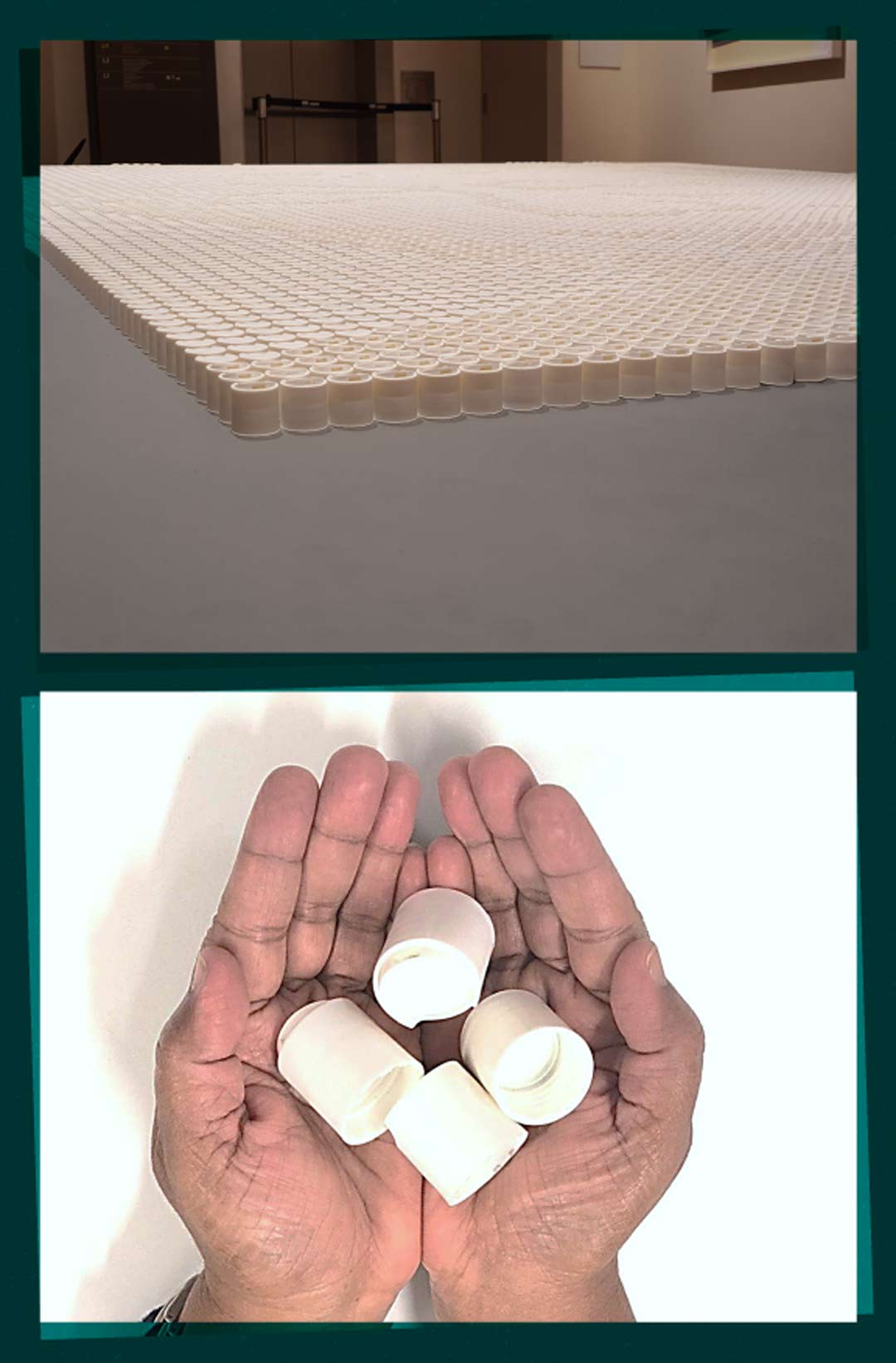

For instance, the museum bought additional shampoo bottle caps used in Jason Wee’s Self-Portrait (No More Tears Mr. Lee) when it was acquired. The work is made out of 8,000 such plastic caps placed individually on an angled pedestal, and some are strategically opened to create an image of Singapore’s late founding prime minister. Spares were necessary because these caps may crack over time due to the material and may not be easily replaced if the design was no longer on sale by then. The modern materials often used in contemporary art may be readily available today but obsolete tomorrow, says Nahid.

“The works are collected to be exhibited and preserved for 50 years and more. That is something that makes conservation difficult,” she adds. “It is still common to buy CDs and DVD players today, but when the work is exhibited in 5 to 15 years later, do we still have them?”

Self-Portrait (No More Tears Mr. Lee) (top) and the bottle caps which form the work (bottom).

For all their time spent fussing and worrying over an artwork, conservators and collections manager are rewarded with the rare opportunity to get up close with pieces that the public usually only gets to see from a distance. It’s one of the reasons why Joanne loves her job.

“A majority of the National Collection is not on display so whatever you see in the museums is a very, very small sample. We see everything. That’s the very beautiful part of being in collections management,” she says.

And if there is one thing Joanne has learnt from her intimate view of contemporary art, it is that nothing is permanent.

“Everything will degrade, it’s just a matter of time,” she says. “You know that it is not going to last forever, but within our capacity we try to preserve it as long as possible for the next generation to see.”

Curious to learn more about what goes on inside the HCC? Find out more here. Also follow SAM’s Facebook and Instagram pages to catch up on the latest updates on its upcoming exhibitions and events, and art collection.